In rehabilitation, implementing smart practices is essential for achieving ideal outcomes. Evidence-based rehabilitation programs incorporate the best available research, expert skills, and patient preferences, ensuring a holistic approach to improving outcomes and recovery. This article discusses the importance of these programs and how they contribute to making rehabilitation more effective.

What are evidence-based rehabilitation programs?

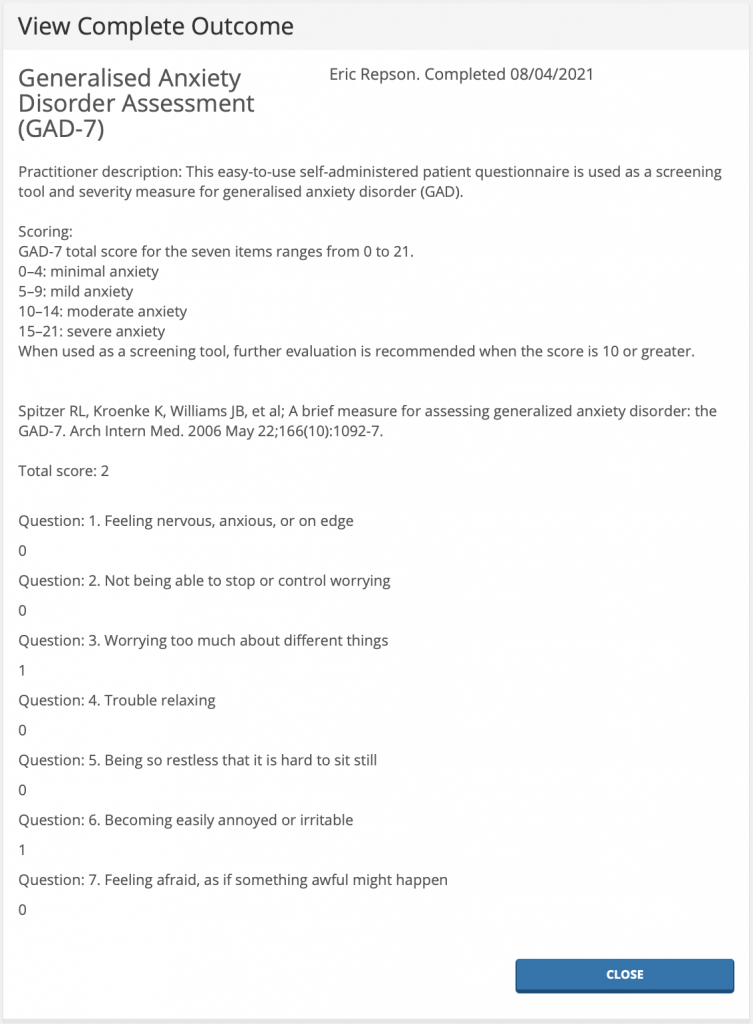

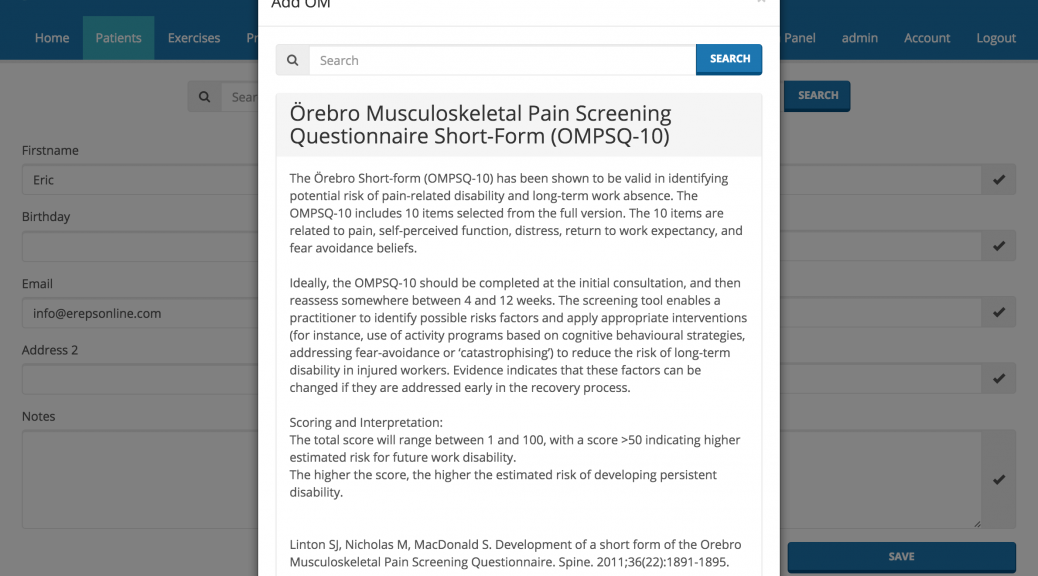

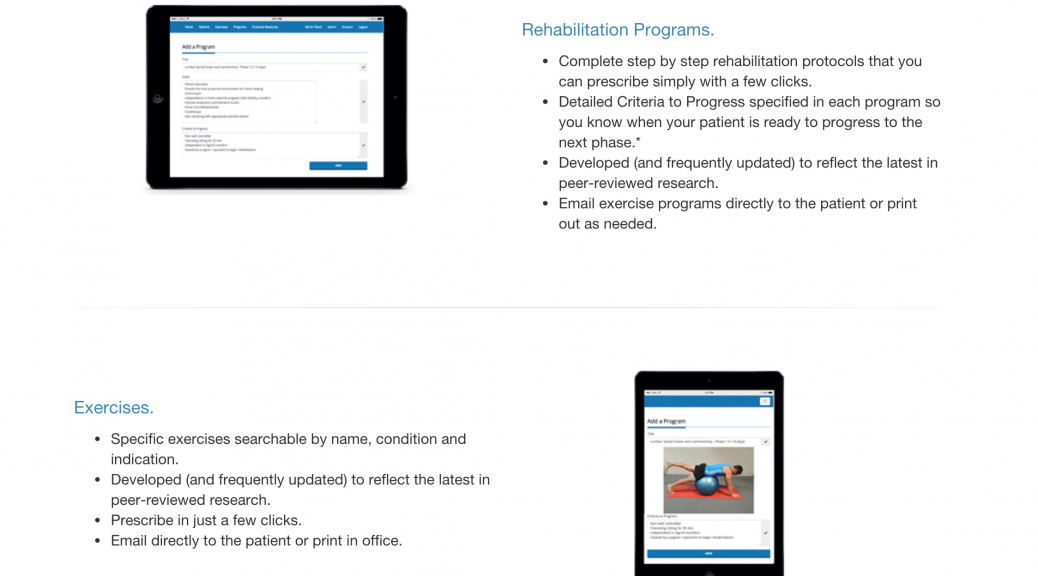

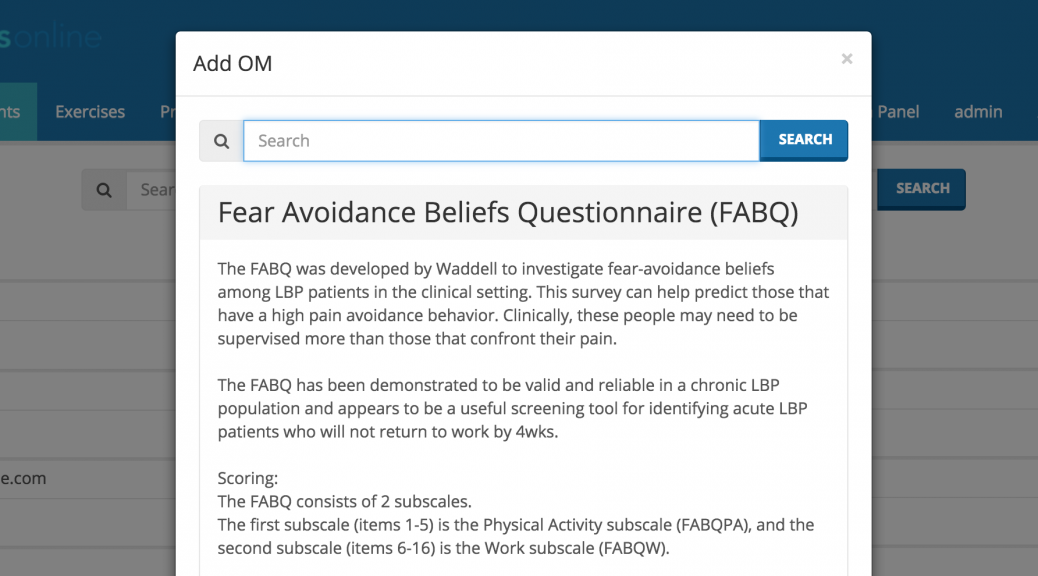

Evidence-based rehabilitation programs are structured around strong research findings that inform and guide their methods. These programs follow established guidelines tailored to specific problems or populations, ensuring that the care provided is not only of high quality but also matches the specific needs and circumstances of individual patients. By focusing on best practices proven through scientific investigation, these programs aim to provide the most effective interventions.

Key Benefits of Evidence-Based Programs

Improved Patient Outcomes: Numerous studies have consistently shown that evidence-based rehabilitation programs result in higher recovery rates and overall better outcomes for patients. Strategies that are used with evidence of their effectiveness significantly increase the chances of successful rehabilitation.

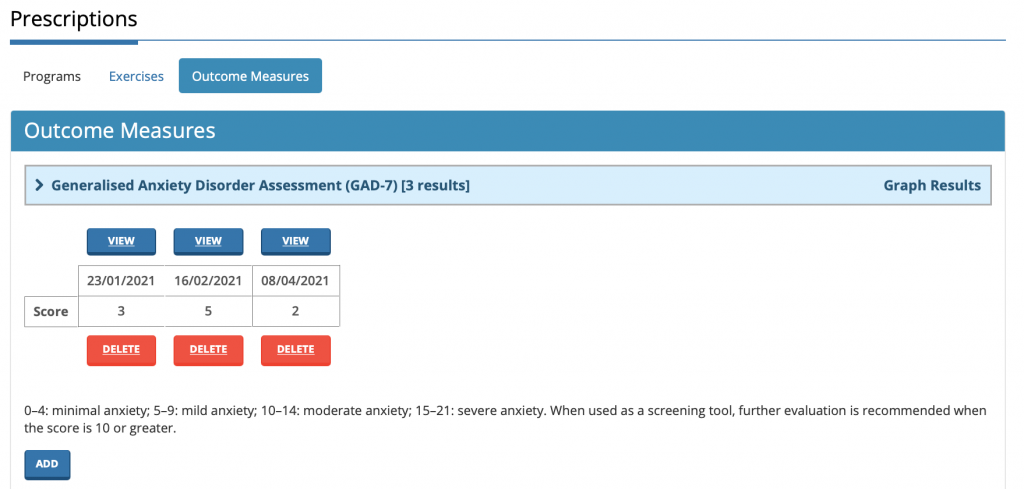

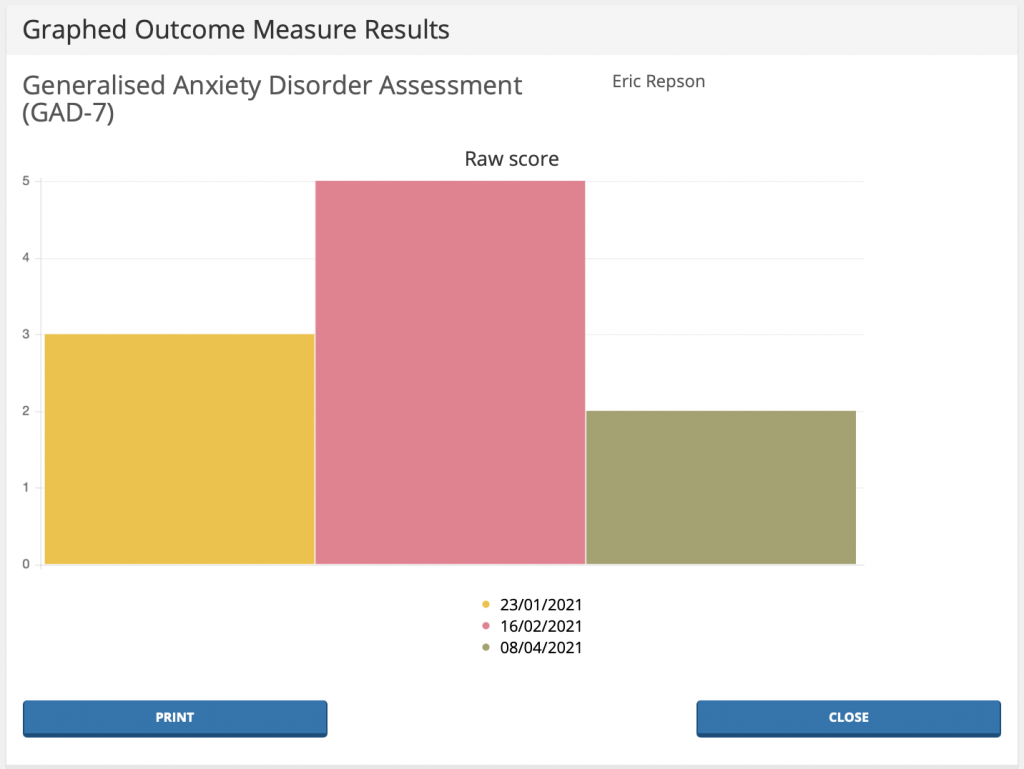

Standardization of Care: One of the main benefits of evidence-based practices is the establishment of standardized protocols. This consistency ensures that patients receive high-quality care, regardless of the particular clinic or facility. Additionally, standardized approaches make it easier to track patient progress over time, simplifying the identification of successful interventions and areas in need of improvement.

Increased Clinician Confidence: When clinicians use evidence-based methods, they have reliable information and data to guide their clinical decisions. This solid foundation helps them gain more confidence in their care, which ultimately leads to a more assured and competent approach to patient treatment. Therapist confidence can influence the therapeutic relationship, creating a more positive environment for patient recovery.

Continuous Improvement: Evidence-based rehabilitation programs are dynamic; they can be regularly updated in response to new research findings. This commitment to incorporating the latest evidence ensures that clinicians stay informed about the most effective and contemporary best practices in rehabilitation medicine. As new studies emerge, programs evolve to include new insights, continually enhancing the quality of care provided to patients.

In summary, the integration of evidence-based rehabilitation programs is crucial for advancing patient care and promoting ongoing growth in the healthcare field. By adopting these practices, clinicians are empowered to provide high-quality care based on strong scientific evidence. This approach not only promotes better outcomes for patients but also contributes to a culture of continuous learning and improvement in rehabilitation settings. As the field of rehabilitation evolves, evidence-based programs will play a vital role in shaping effective and efficient care strategies.